Not an Economic Question but a Question about Economics

Why does thoughtful academic debate surrounding Modern Monetary Theory remain conspicuously absent among economists?

Why Can’t We Discuss MMT?

I expect many people have pondered this, but should we talk about why a thoughtful debate among economists around analyses advanced by Modern Monetary Theory never happens?

Why do critics seem incurious and impatient, moralizing instead of analyzing? Why are MMT ideas routinely and inaccurately caricatured and dismissed as naive or reckless? And why do those dismissals feel so charged and oddly personal?

It is especially notable — and weird — because MMT’s central claims are neither speculative nor exotic. They are descriptive claims about monetary operations: how government spending occurs, how central banks clear payments, and how public deficits and surpluses map onto private-sector balance sheets.

Economic debates, both within the profession and among public policy actors and advocates, are normally polite and typically conducted at the margins, even when grappling with sharp methodological disputes. Covid provided many examples of the kinds of differences that tend to be debated. There were the monetary policy debates: Should interest rates rise faster or slower? Is inflation transitory or persistent? Has r*, the neutral rate, risen? Should the central bank tolerate more inflation to protect employment? There were the fiscal policy debates: What level of deficit spending is tolerable? Should stimuli be front-loaded or phased? Should we adjust tax rates? And occasionally there were labor market debates: Is the NAIRU lower than we thought? Are wage pressures structural or cyclical? Is labor market tightness inflationary?

Inconvenient Truths

Perhaps the problem is that most of the time, MMT considerations necessitate debates not at the margins, but ones that go to the heart of the matter, that, per force, contest assumptions, values, and priorities by examining real-world economic operations and outcomes. How, for instance, could the undeniable real world effects on private sector balance sheets of the Clinton administration’s determined effort to balance the government’s budget fail to effect the establishment’s view of government deficits and debt? A picture should be worth a thousand words.

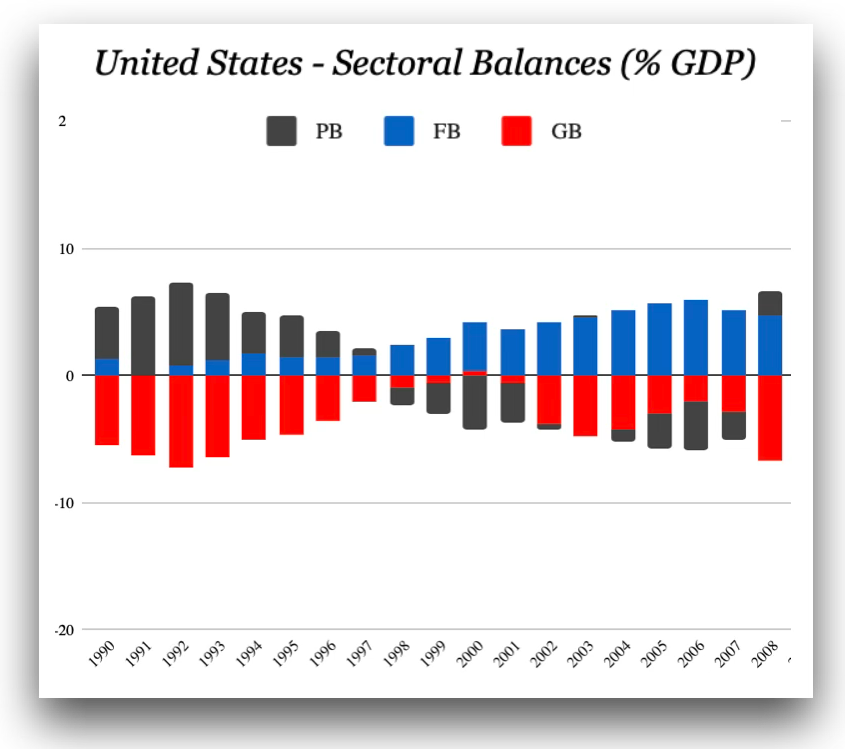

It is an accounting identity, not a debatable theory, that the deficits and surpluses of the three sectors of any nation’s account — the government sector, the domestic private sector, and the foreign sector — must sum to zero. From 1993 to 2000, the Clinton administration, in the name of fiscal “responsibility,” was determined to bring the government’s budget from deficit into surplus. This forced domestic households, businesses and organizations into deficit — from a healthy surplus of almost 7% of GDP to a debilitating deficit of more than 4% of GDP, fueling the 2001 recession and setting the stage for the 2008 sub-prime mortgage crisis.

It seems fair — important even — to ask why, on this critical matter of public finance (a leading example among many) the economics establishment seems so hell-bent on defending ideas related to government budgets and fiscal policy with negligible empirical support. Indeed, how could a whole set of economic theories that eschew irrefutable evidence continue to prevail, generation after generation?

Starting with the “how,” somewhere along the line, economics became the “science” of optimal decision-making, anchored to the myth of the market as a self-regulating, self-equilibrating mechanism, replacing explanations of real-world phenomena with rational decision-making “rules.” These rules, in turn, came to depend on formal, not empirical proofs — the stuff of “pure” mathematics — technique over explanation, elegance over relevance.

Dogma versus Hypotheses

Digging a little more deeply, privileging technique has the further effect of infantilizing the uninitiated, making challenges to orthodoxy seem primitive and naive. Moreover, to be certified as worthy and competent, the neophyte economist must learn the apparently scientific, mathematical language of her elders. Not unlike rituals of a priesthood, the translation of theory into mathematical formalism insulates orthodox ideas while becoming a screening device, keeping out the curious, the skeptical, and other agents of change.

Simultaneously, by making an overwhelming case for limiting the role of government in the economy (a profoundly political ideological position), neoclassical theory pretends to be apolitical, separate from the push and pull of politics. Combined with the myth about the power of the market to self-regulate and optimize, orthodox economic beliefs are both reified and insulated by being — putatively only — both “scientific” and “above politics.”

I am not the first to note that the economics profession is a special sort of priesthood in which belief, technique, and language combine to confer a distinctive, life-long identity. Indeed, for most economists, the discipline is not merely a set of analytical tools. Often performed at the intersection of the academy, enterprises, and government, it is a professional identity developed over years of training, teaching, and peer validation. That identity, in turn, rests on shared beliefs and a set of constraints, matters that are neither questioned nor debated. Especially telling may be those constraints, which function as a kind of intellectual celibacy that assumes a natural order, that is defended against heresy, and that at least countenances and often requires abstinence from contending perspectives.

One could be excused for thinking that MMT’s operational claims have implications that, for market fundamentalists, feel promiscuous or licentious. It is true that they question the ostensibly prudent loanable-funds view of government finance. They reframe presumably reckless public debt as a record of net private savings rather than a burden irresponsibly imposed on future taxpayers. They insist that a currency-issuing government faces real resource constraints, but not financial ones. And they treat unemployment not as an inevitable, unfortunate equilibrium outcome but as a policy failure.

On the other hand, one might imagine that the ramifications of MMT’s claims would be liberating because they imply that some of the most commonly invoked constraints in public economic discourse — “we can’t afford it,” “markets will punish us,” “there is no alternative” — were never binding in the way they have been presented and assumed. But one can also imagine that for a member in good standing of the economic priesthood who has adhered to this intellectual celibacy as a kind of moral framework, who has relied on it as a sign of seriousness, rigor, and credibility, especially in offering policy advice, such a realization could question everything:

“What exactly have I been doing… or not been doing?”

Real World Economists

Reclaiming the profession requires two things: The first is an open-minded, inclusive study of real inevitably messy events, of real inevitably complicated people, of real inevitably entangled political and economic structures, and of real monetary systems and operations. The second is a commitment to keep the economy embedded in the institutions of the society it purports to provision, thereby also shaped by the values and aspirations of those societies.

At the very least, economists need to give up the solipsistic presumptions of market fundamentalism. Economics could be, should be, a necessarily imperfect, adaptable, always improvable set of tools, invented by humans, in support of sustainable prosperity for each, on a sustainable planet for all.

Should that be so hard? It could even be lively, creative, generative, optimistic, and fun.

This article was originally published on Susan Borden’s Substack and is reproduced here with the author’s permission.