On The Nature of Money and Why It Matters

An historical and theoretical overview of money and the policy implications of having an accurate understanding of its nature.

The money question has long backgrounded a history of debate in economics. After observing how economic debates usually evolve, I have concluded that a large part of the persistent confusion that permeates economic discourse stems from a poor understanding of the nature of money. That confusion is not benign. It bleeds directly into how people think government finance works, what ‘borrowing’ means, what inflation control requires, and what policies are deemed possible.

Money is one of those fundamental creations of society that everyone uses but few stop to question. Put simply, money is that which we use to pay for things. However, the full explanation of money is rather more complex. Is money essentially a physical commodity that emerged from primitive barter, with value grounded in metal and market exchange? Or is it a social credit instrument, a token of debt shaped by law and state authority? These are the two broad camps that still sit behind many modern arguments and the two views on money I intend to consider here.

The Commodity or Metallist Story

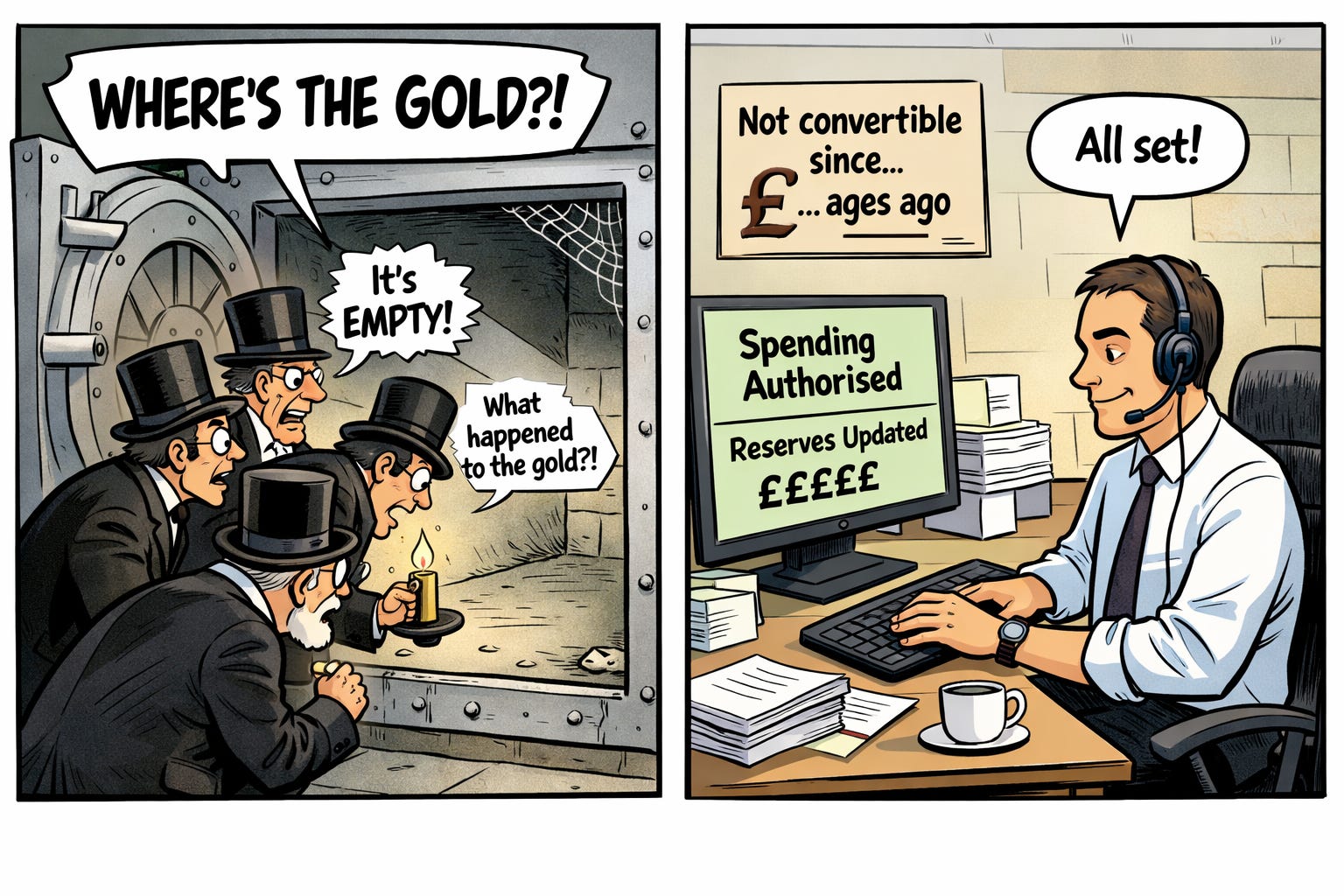

The commodity or metallist story is familiar. In the beginning, there was barter. People swapped goats for grain or shoes for fish until the double coincidence of wants made exchange awkward, so societies converged on a common medium of exchange via a form of natural selection. Over time, this became gold, silver, salt, coins of set weight and purity, and later banknotes as claims on the ‘real’ underlying commodity money.

In this story, money’s value is intrinsic or anchored in a commodity, and the state is at most a certifier that stamps coins and restrains fraud. It is easy to see why this view lends itself to sound money doctrines. If money is scarce and external to political economy, then government must first find it via tax or borrowing before it can spend. Fiscal policy should largely behave like a household budget. If inflation threatens, then unemployment becomes an acceptable, even necessary, buffer stock to restrain wages and anchor prices because it’s viewed as a natural consequence of the dynamics of the labour and money markets.

The Credit and Chartalist Story

The credit and chartalist story flips the origin myth on its head. Money did not emerge from barter at all. It emerged as a unit of account and a system of IOUs. Alfred Mitchell-Innes put it with brutal clarity: “Credit and credit alone is money”, and “credit is the correlative of debt”.

In this view, money is not a ‘thing’ but an accounting relationship. A financial asset is someone else’s liability and a payment is not the movement of a real physical substance, but the discharge and creation of obligations within an accounting ledger. In essence, it’s credits and debits all the way down.

Once you take that seriously, modern state money becomes much easier to understand. The state no longer promises to convert its IOU into a commodity upon redemption. It promises something more basic and more powerful: it promises that its liability will be accepted back in settlement of our own liabilities to the state. Taxes are the most general, non-negotiable of those liabilities.

This is the chartalist insight captured by Knapp and endorsed by Keynes. Money is a creature of law, and the money of a state is “that which is accepted at public pay offices”. Adam Smith even acknowledged the mechanism plainly when he noted that a ‘Prince’ can give value to paper by requiring taxes to be paid in it.

The Aggregate and Institutional Perspective

None of this means individuals go to work merely to pay taxes. It’s obvious to anyone that we work and sell in order to consume and live a nice life. The point is aggregate and institutional. Taxes create a baseline demand for the unit of account, and state spending supplies it. Network acceptance then scales it through the economy, and at each node in the chain of production and exchange, state money is accepted because it is universally usable to extinguish obligations in the state unit, directly or indirectly.

Government Finance Misconceptions

This is where the crucial misconception about government finance enters. If money is state credit, it makes no sense to imagine the government collecting tax revenue to then spend, or borrowing its own currency via bond issuance and then spending it. The state’s money is its own IOU. It is not a pre-existing asset the issuer can collect, store, and later redeploy.

When taxes are paid, the state does not acquire money. It extinguishes its own liability. Taxation is not directly fungible with real resources, but functions to facilitate, via an inductive process, the transfer of real production from private use to public use. It creates fiscal space only to the extent it reduces private spending and frees real resources from private use so the state can purchase them without causing inflation.

The same logic applies to bonds. Bond issuance does not fund spending in the way a household or firm borrows to obtain money it cannot issue. It is a swap of state liabilities, typically exchanging an overnight, floating-rate monetary IOU for a longer-duration, fixed-rate IOU. Thinking of this as ‘borrowing in order to spend’ is a category error.

It is like imagining someone can finance their future spending by collecting and hoarding their own handwritten IOUs after others have returned them. Once returned, the IOU ceases to exist as a spendable object. The piece of paper might still exist, but the actual abstract ‘thing’ that constituted it as ‘money’ no longer does. Once the consolidated state sector redeems one of its IOUs, it doesn’t matter whether the Treasury holds a positive account balance with its central bank — it no longer functions as money.

Government Spending and Public Debt

To really drive this point home, it is the act of government spending itself that constitutes ‘borrowing’ in the strict accounting sense. When the state spends, it issues a new monetary liability into the economy, and someone must accept and hold it. A creditor–debtor relationship is created at that moment. Public debt rises at the point of spending, not at the later point of security issuance. Bond markets do not grant the state permission to spend — they just decide how they want to hold state liabilities that already exist.

Competing Policy Frameworks

These competing ontologies of money lead to competing policy frameworks. If you treat money as scarce commodity-like finance, deficits are moralised, budgets are forced towards balance (either all the time or over the economic cycle), and unemployment becomes an inflation tool.

If you understand money as state credit, the constraint is never solvency in the state’s own currency but inflation and real productive capacity. The policy question becomes how to use the monetary system to secure full employment and public purpose without bidding beyond what the economy can supply.

That is why the inflation anchor matters. Orthodoxy largely chose an unemployment buffer stock, formalised in concepts like the NAIRU. A chartalist and MMT approach instead proposes an employed buffer stock through a Job Guarantee, anchoring the price level without forcing idleness and decay as the stabilisation mechanism.

Conclusion

If money is understood as what it really is — an institutional tool and a credit-debt social relationship monopolised by state authorities — then we can shape it to serve society, rather than constraining ourselves to serve a mythology. The debate stops being “can we afford it?” and becomes “do we have the real resources, and what should they be used for?”

This article was originally published on Jamie Smith’s Substack and is reproduced here with the author’s permission.